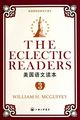

BY JOHN RUSKIN

John Ruskin (1819-1900): An English author. His most important works are "Modern Painters," a treatise on the principles of art, and "The Seven Lamps of Architecture," a treatise on the principles of architecture. Besides art criticisms, Ruskin wrote many books on ethical, educational, and political subjects.

This selection is from "Modern Painters."

profitless or unnecessary to review briefly the nature of the three 10John Ruskingreat offices which mountain ranges are appointed to fulfill, in order to preserve the health and increase the happiness of mankind.

Their first use is of course to give motion to water. Every fountain and river, from the inch-deep streamlet that crosses the village lane in trembling clearness, to the massy1 and silent march of the everlasting multitude of waters in Amazon or Ganges, owe their play and purity and power to the ordained elevations of the earth. Gentle or steep, extended or abrupt,1 Massy: massive; forming or consisting of a large mass.

some determined slope of the earth"s surface is of course necessary before any wave can so much as overtake one sedge in its pilgrimage.

How seldom do we enough consider, as we walk beside the margins of our pleasant brooks, how beautiful and wonderful is that ordinance1, of which every blade of grass that waves in their clear water is a perpetual sign, that the dew and the rain fallen on the face of the earth shall find no resting place; shall find, on the contrary, fixed channels, traced for them from the ravines of the central crests down which they roar in sudden ranks of foam, to the dark hollows beneath the banks of lowland pasture around which they must circle slowly among the stems and beneath the leaves of the lilies.

Paths are prepared for them, by which, at some appointed rate of journey, they must evermore descend, sometimes slow and sometimes swift, but never pausing. The daily portion of the earth they have to glide over is marked for them at each successive sunrise, the place which has known them knowing them no more; and the gateways of guarding mountains are opened for them in cleft and chasm, none letting2 them in their pilgrimage; and, from far off, the great heart of the sea calls them to itself.

It is easy to conceive how, under any less beneficent dispositions of their masses of hill, the continents of the earth might either have been covered with enormous lakes or have1Ordinance: law.

2Letting: delaying; hindering,- an old meaning of the word.

become wildernesses of pestiferous marsh, or lifeless plains upon which the water would have dried as it fell, leaving them for great part of the year desert. Such districts do exist, and exist in vastness: the whole earth is not prepared for the habitation of man; only certain small portions are prepared for him.

And that part which we are enabled to inhabit owes its fitness for human life chiefly to its mountain ranges, which, throwing the superfluous rain off as it falls, collect it in streams or lakes, and guide it into given places and in given directions; so that men can build their cities in the midst of fields which they know will be always fertile and establish the lines of their commerce upon streams which will not fail.

Nor is this giving of motion to water to be considered as confined only to the surface of the earth.

In the Bernese Alps, Switzerland

A no less important function of the hills is in directing the flow of the fountains and springs from subterranean1 reservoirs. There is no miraculous springing up of water out of the ground at our feet, but every fountain and well is supplied from a reservoir among the hills, so placed as to involve some slight fall or pressure, enough to secure the constant flowing of the stream.

And the incalculable blessing of the power given to us in most valleys, of reaching by excavation some point whence the water will rise to the surface of the ground in perennial2 flow, is entirely owing to the concave disposition of the beds of clay or rock raised from beneath the bosom of the valley into ranks of inclosing hills.